Organising information: trees#

This chapter introduces a new data structure for defining hierarchical relations: the tree. The historic hero introduced in these notes is Gabriel García Márquez, one of the most notable writers in Spanish of the 20th century. One of his novels (One Hundred Years of Solitude) is used in this chapter to introduce the way trees (as a data structure) can be used to understand a story. Moreover, even to structure a text.

Note

The slides for this chapter are available within the book content.

Historic hero: Gabriel García Márquez#

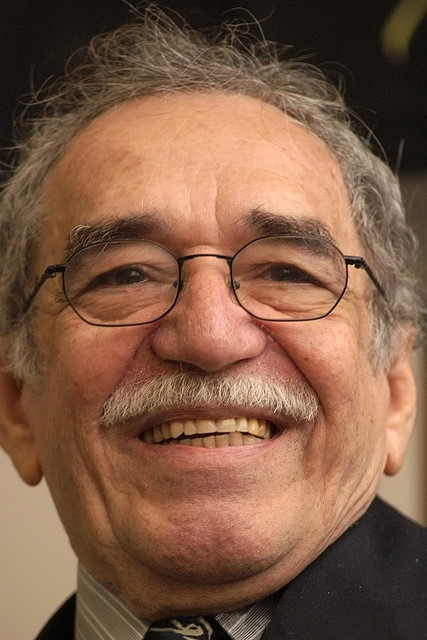

Gabriel García Márquez (shown in Fig. 42) was a Colombian novelist, and he was one of the most notable writers in Spanish of the 20th century. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982. As a journalist, he wrote several non-fictional works. However, he is mainly known for his novels, such as Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude in English) and El amor en los tiempos del cólera (Love in the Time of Cholera in English).

Several of his works mention the fictional town of Macondo. This city is the primary setting of one of his books, i.e. One Hundred Years of Solitude, which narrates the story of the Buendia family. In particular, the story introduces the life of seven different generations of people of the same family. It follows its adventures and, often, misfortunes.

In the Italian edition of this novel, published by Mondadori [GM19], the publisher inserted a family tree of the various generations at the beginning of the book. While it provides a few spoilers about future events, it is instrumental in following the family’s story since several Buendia people often share the same name. Thus, the family tree is a handy device that facilitates the reader to follow the story, understanding to whom the narrator is referring.

Fig. 42 A portrait of Gabriel García Márquez. Picture by Jose Lara, source: Wikipedia.#

García Márquez is the second Latin American writer we have used in this course. We use him to introduce specific topics related to the Computational Thinking and Computer Science domains. For example, trees (such as family trees) are particular kinds of structures that allow one to define a hierarchy of values useful for a plethora of different tasks or computations.

Where is the tree?#

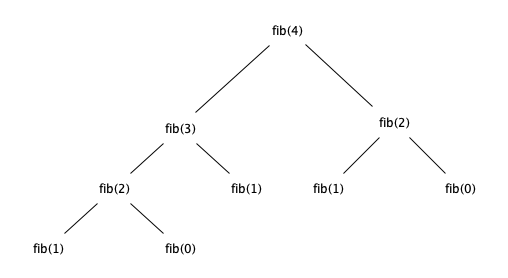

It is not the first time we have adopted a tree for describing something. In particular, in the Chapter Dynamic programming algorithms, we used a tree (reprised in Fig. 43) to show the recursive calls’ execution to the function implementing the algorithm to find the Fibonacci number.

Fig. 43 The tree that describes the various recursive calls for calculating the Fibonacci number at the 4th month, as described in Chapter Dynamic programming algorithms.#

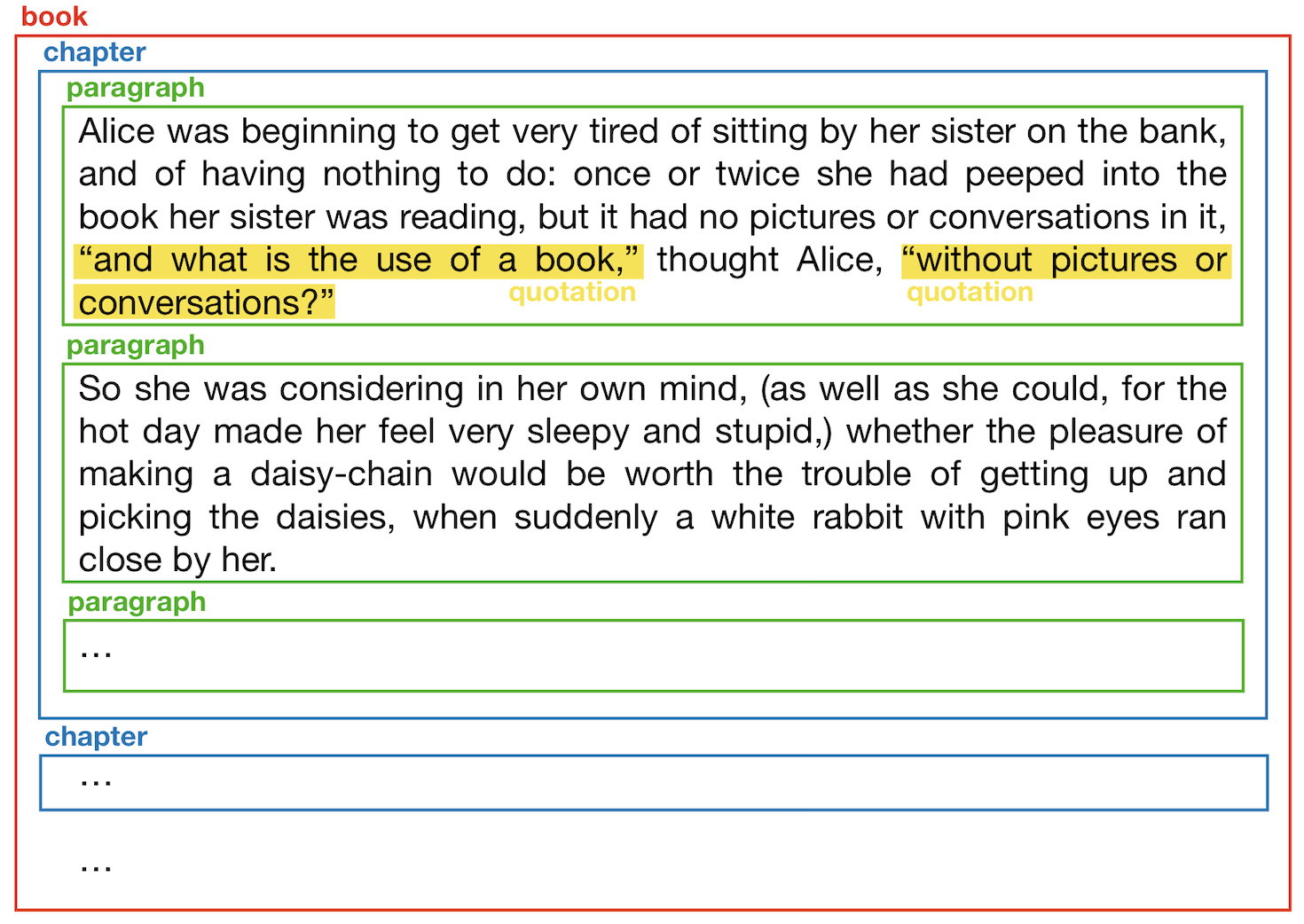

A Digital Humanist has to deal with trees in daily tasks. For instance, marking a text up using a specific markup language, i.e. a language for associating particular roles to the various parts of a text, is an activity one must address several times. Trees (as data structures) are the grounds for such a marking activity.

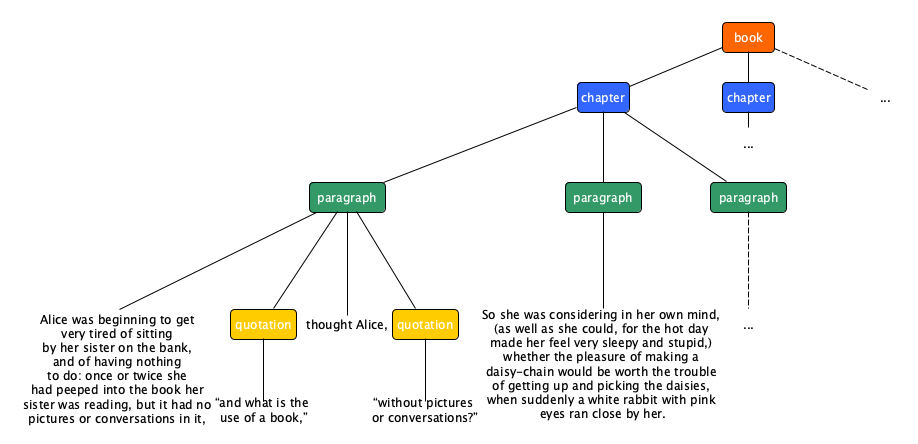

Marking up a text is something that, even implicitly, we do when we look at a piece of text, such as a novel. For instance, please consider the following excerpt from the first chapter of Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll [Car66]:

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?”

So she was considering in her mind, (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid,) whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a white rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

Each part of the text of the content above is organised precisely. Specific blocks of text are contained in paragraphs organised within chapters that finally compose the book.

Fig. 44 The first two paragraphs of Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland marked up with basic textual structures.#

Fig. 45 The tree that describes the containment of the various structures in the initial text of Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland.#

Besides, the text within each paragraph can contain additional structures, such as quotations when a character is speaking. Fig. 44 shows all these structures. The main structure (i.e. book) is described as a box containing several boxes labelled chapter, each containing other boxes labelled paragraph, and so on. Enclosing part of a text within a labelled box is called markup. Appropriate markup languages have been defined to enable such annotations on a text.

<html>

<head>

<title>Alice's Adventures in Wonderland</title>

</head>

<body>

<section role="doc-chapter">

<p>

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by

her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do:

once or twice she had peeped into the book her

sister was reading, but it had no pictures or

conversations in it, <q>and what is the use of a

book,</q> thought Alice, <q>without pictures or

conversations?</q>

</p>

<p>

So she was considering in her own mind, (as well as

she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy

and stupid,) whether the pleasure of making a

daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up

and picking the daisies, when suddenly a white

rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

</p>

<p>...</p>

</section>

<section role="doc-chapter">...</section>

...

</body>

</html>

The organisation mentioned above of boxes describes a clear hierarchy between them. For example, the bigger one (i.e. book) contains smaller ones (i.e. chapters), those include even smaller ones (i.e. paragraphs) and so on. When we are in the presence of such a hierarchical organisation of non-overlapping items, we can abstract it as a tree, as shown in Fig. 45.

Languages such as the one provided by the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) and the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) are peculiar exemplars of markup languages. They allow one to construct hierarchies of markup elements for structurally and semantically annotating a text. For instance, Listing 50 shows a possible HTML representation of the quotation mentioned above from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Trees#

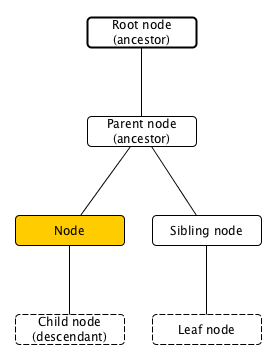

A tree is a data structure that simulates a hierarchical tree composed of a set of nodes related to each other by a particular hierarchical parent-child relation. As shown in Fig. 46, this data structure usually follows a top-down presentation order, contrary to the actual real organisation of the plant.

Fig. 46 A tree with the typical jargon of its nodes considering the one highlighted in yellow as the focus. In this figure, the bold border identifies the tree’s root node (i.e. the only node without any parent). Instead, the dashed border is used to indicate the leaf nodes of a tree (i.e. those nodes that do not have any children).#

The originating (or starting) node is the root node, placed at the very top of the tree. Instead, the terminating nodes, called leaf nodes, are placed at the bottom. Considering a node of a tree, e.g. the yellow one highlighted in Fig. 46, we can name precisely all the other nodes surrounding it. In particular:

the parent node of a given one is a node directly connected to another one when moving close to the root node;

a child node of a given one is a node directly connected to another one when moving away from the root node;

a sibling node of a given one is a node that shares the same parent node;

an ancestor node of a given one is a node that is reachable by following the child-parent path repeatedly;

a descendant node of a given one is a node that is reachable by following the parent-child path repeatedly.

In Python, a tree is a set of nodes linked together according to parent-child relationships. Each tree is identified by its root node, which is unique. While there is no built-in implementation of the tree data structure in Python, some external packages are very well-suited for the task. Among those, one of the most famous ones is anytree.

This package allows one to create a tree node using the constructor Node(name, parent=None). Thus, each node must specify a name that can be any Python object, such as a string, and a parent node. If the parent is not specified, it will assume None as value, which implicitly defines it as the tree’s root node. In anytree, the constructor is the primary mechanism for determining a tree by merely stating the parent relations during the definition of new nodes.

It is worth mentioning that a parent node includes its children in a precise order. In particular, the order of insertion creates a kind of ordered list between all the sibling nodes. For instance, in the example in Listing 2, paragraph_1 comes before paragraph_2 in the siblings of the node body.

The advantages of using anytree are that it makes available many facilities for accessing various information associated with a node, using some variables associated with the class Node. The main variables are:

<node>.namereturns the object used as a name when creating<node>;

<node>.childrenreturns a tuple listing all the children of<node>;<node>.parentreturns the parent of<node>;

<node>.descendantsreturns a tuple listing all the descendants of<node>(including its children);

<node>.ancestorsreturns a tuple listing all the ancestors of<node>(including its parent);

<node>.siblingsreturns a tuple listing all the siblings of<node>;<node>.rootreturns the root node of the tree containing<node>.

as part of the material of the course.# 1from anytree import Node

2

3book = Node("book")

4chapter_1 = Node("chapter", book)

5chapter_2 = Node("chapter", book)

6

7paragraph_1 = Node("paragraph", chapter_1)

8text_1 = Node("Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by "

9 "her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: "

10 "once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister "

11 "was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations "

12 "in it, ", paragraph_1)

13quotation_1 = Node("quotation", paragraph_1)

14text_2 = Node(""and what is the use of a book,"", quotation_1)

15text_3 = Node(" thought Alice, ", paragraph_1)

16quotation_2 = Node("quotation", paragraph_1)

17text_4 = Node(""without pictures or conversations?"", quotation_2)

18

19paragraph_2 = Node("paragraph", chapter_1)

20text_5 = Node("So she was considering in her own mind, (as well as "

21 "she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy "

22 "and stupid,) whether the pleasure of making a "

23 "daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up "

24 "and picking the daisies, when suddenly a white rabbit "

25 "with pink eyes ran close by her.", paragraph_2)

26

27paragraph_3 = Node("paragraph", chapter_1)

28text_6 = Node("...", paragraph_3)

29text_7 = Node("...", chapter_2)

30text_8 = Node("...", book)

We can update the variables defining the children and the parent of a node by assigning to them a particular collection (e.g. a list or a tuple) of nodes. For instance, we can invert the ordering of the first two paragraphs defined as children of the first chapter node in Listing 51 as shown in Listing 52.

1chapter_1.children = (paragraph_2, paragraph_1)

Also, it is possible to visualise the tree graphically on the shell by using appropriate tree renderers, described by the class RenderTree included in the anytree package. Once imported, one can create a new RenderTree object by specifying a node as input (e.g. the root node of the tree). Then one can print such a new renderer object to obtain a textual representation of the tree, as shown in Listing 53.

1from anytree import RenderTree

2

3renderer = RenderTree(book)

4print(renderer)

5

6# Node('/book')

7# ├── Node('/book/chapter')

8# │ ├── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph')

9# │ │ ├── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/Alice was…')

10# │ │ ├── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/quotation')

11# │ │ │ └── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/quotation/"and…')

12# │ │ ├── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/ thought Alice, ')

13# │ │ └── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/quotation')

14# │ │ └── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/quotation/"without…')

15# │ ├── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph')

16# │ │ └── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/So she was…')

17# │ └── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph')

18# │ └── Node('/book/chapter/paragraph/...')

19# ├── Node('/book/chapter')

20# │ └── Node('/book/chapter/...')

21# └── Node('/book/...')

References#

Lewis Carroll. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Macmillan and Co, London, United Kingdom, 1866. URL: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Alice%27s_Adventures_in_Wonderland_(1866).

Gabriel García Márquez. Cent'anni di solitudine. Mondadori, Milan, Italy, 2019. ISBN 978-88-04-67598-3. OCLC: 1124897257.