Organising information: unordered structures#

This chapter introduces the main concepts related to some of the most important data structures for creating and handling sets and dictionaries. The historic hero introduced in these notes is Jorge Luis Borges, considered one of the most famous Argentinian writers of the past century. Among his vast work, he wrote several short stories focused on exploring mathematical concepts and limits.

Note

The slides for this chapter are available within the book content.

Historic hero: Jorge Luis Borges#

Jorge Luis Borges, shown in Fig. 29, was an Argentine short-story writer, poet, and essayist, who produced several works laying between philosophical literature and fantasy genre. In his short novels, he explored several aspects and situations related to dreams, labyrinths, libraries, mirrors, the notion of infinity, and religions, among others.

One of his most known stories is entitled The Library of Babel [Bor41]. In this short piece, he describes an incredibly big library, made of hexagonal rooms. In four of the walls of each room, there were 20 bookshelves (5 bookshelves for each wall). Each bookshelf contained 35 books. Each book counted precisely 410 pages of 40 lines each, and each line contained precisely 80 characters. From one of the two empty walls, one could access a hallway with two small rooms (one where to sleep standing up, the other with a bathroom) and the stairs to get to higher hexagonal rooms. The whole library contained all the books ever written by using every possible combination of 25 characters: 22 letters, the period, the comma, and the space. Of course, the main parts of the books contained a nonsense sequence of characters, while others (or even limited amounts of them) were, indeed, describing situations using intelligible language. However, even between those, some books negated the statements of the others explicitly. Thus, the narrator suggested that we are in the presence of all the possible written books. Even when they make sense, books are useless because they describe any likely fact from all the possible perspectives. Thus, there is no absolute truth available, and all the possibilities are possible.

Fig. 29 A picture of Jorge Luis Borges at L’Hôtel in Paris. Source: Wikimedia Commons.#

The opening sentence is of particular interest: “[the Library] is composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries”. In this passage, the narrator suggests an infinite number of books in the library, contained in an endless number of rooms. However, is this the case?

Understanding infinity is a matter of personal perception of things. Often, we refer to an infinite amount of something (time, space, etc.) when we are speaking about a huge mass of stuff. Stuff that is delimited by some physical or social constraints. The Library of Babel falls in these kinds of situations. Even if the narrator explicitly says that the library is infinite, it can contain only 2⋅101834097 books [Joy16]. We can obtain the previous number by considering all the possible combinations of the finite set of characters. Characters that can appear in all the 40 pages in all the books the library contains. And this number exists, even if it is so big that it is not manageable by our mind and, thus, we tend to identify it to infinity, while it is not. To support this non-infinity, someone has also tried to implement the Library as a digital space.

Of course, mathematical infinity exists as an abstract concept – e.g. think about the set of all the prime numbers, which is an infinite set. However, a computer is physically limited in space and has a limited set of resources. Thus, a computer can only approximate the concept of infinity. For instance, we can implement an algorithm that runs forever in a specific programming language. However, if we ask an electronic computer to run it, we will see that it may stop anyway due to external reasons: a blackout, the breaking of some hardware necessary for the correct execution of its processes, etc.

Considering the applications and implementations of computational systems, we must be aware that infinity (e.g. the infinite tape of a Turing Machine, the endless execution of an algorithm, etc.) is an illusion. Instead, it is just a theoretical tool to sketch out possible borders for real-world problems.

A clarification: classes and methods in Python#

In programming languages, classes are extensible templates for creating objects having a specific type. In practice, all the values (e.g. numbers and strings) and other entities (e.g. lists and stacks) we create are objects of a specific class. The creation of objects of a specified kind is possible by calling a constructor, i.e. a particular function (e.g. list() for lists) which creates a new object of that class.

The advantage of organising all these types of values as classes is that each object made available a set of methods that allow one to interact with the object itself. A method is a particular function that can be run only if directly called via an object. Their fingertips is structured as follows: <object>.<method>(<param_1>, <param_2>, ...). For instance, methods of the class list define all the operations we have introduced for manipulating lists, e.g. <list>.append(<item>), <list>.remove(<item>), etc.

It is possible to create our classes and methods. However, this topic goes beyond the actual scope of this book. If interested in understanding how to create these items, please refer to the documentation provided in Chapter ch_programming-languages.

Unordered structures#

This chapter will introduce two specific data structures discussed in detail in the following sections, i.e. sets and dictionaries. They are among the most basic and used data structures in algorithms (and, more concretely, in programs). They do not specify any order for their elements. Finally, they do not allow repetitions – i.e. the same value cannot be specified twice.

Sets#

A set is a countable collection of unordered and non-repeatable elements. It is countable because we can use the built-in function len() (introduced some chapters ago, when we talked about lists) for counting the elements it contains. Its elements are unordered because the order of the insertion operations does not provide any cardinality relation among such elements. Finally, its elements are not repeatable because the same value cannot be included twice in the set.

Of course, there exist several real examples of such abstract sets in real-life objects. For instance, in Fig. 30, we show a class of students and a collection of colours. Both of them are concrete objects that are built starting from the abstract notion of a set.

Fig. 30 Two examples of a set in natural objects are a class of students (left) and a collection of colours in a plastic glass (right). Left picture by Uri Tours, source: Flickr. Right picture by Mikel Seijas Alonso, source: Flickr.#

In Python, a new set can be instantiated using the constructor set(). For instance, my_first_set = set() will create an empty set and associate it with the variable my_first_set.

We can execute several operations on sets, in particular:

we use the method

<set>.add(<element>)for adding a new element to the set – for instance, my_first_set.add(34)andmy_first_set.add(15)will add the numbers 34 and 15 to the set – it is worth mentioning that adding an element already included in the set does not add it again;we use the method

<set>.remove(<element>)for removing an element from the set – for instance, my_first_set.remove(34)will remove the number 34, obtaining a set with just the element 15 included in it;we use the method

<set>.update(<another_set>)for adding all the elements included in<another_set>to the current set – for instance, if we have the setmy_second_setcontaining the numbers 1 and 15, my_first_set.update(my_second_set)will add just 1 to the current set, since 15 was already present.

as part of the material of the course.# 1my_first_set = set() # this creates a new set

2

3my_first_set.add(34) # these two lines add two numbers

4my_first_set.add(15) # to the set without any particular order

5# currently my_first_set contains two elements:

6# set({ 34, 15 })

7

8my_first_set.add("Silvio") # a set can contains element of any kind

9# now my_first_set contains:

10# set({34, 15, "Silvio"})

11

12my_first_set.remove(34) # it removes the number 34

13# my_first_set became:

14# set({15, "Silvio"})

15

16# it doesn't add the new elements since they are already included

17my_first_set.update(my_first_set)

18# current status of my_first_set:

19# set({15, "Silvio"})

20

21my_first_set_len = len(my_first_set) # it stores 2 in my_first_set_len

In Listing 34, we show some examples of the use of sets in Python. As in the examples of the previous chapter, we describe with natural language comments the various aspects related to the creation and modification of sets.

Dictionaries#

A dictionary is a countable collection of unordered key-value pairs where the key is non-repeatable in the dictionary. It is countable because we can use the built-in function len() for counting the elements it contains. Its elements are unordered because the order of the insertion operations does not provide any cardinality relation among such elements, similar to sets. Finally, the keys of its pairs are not repeatable because the same key cannot be used twice in the dictionary.

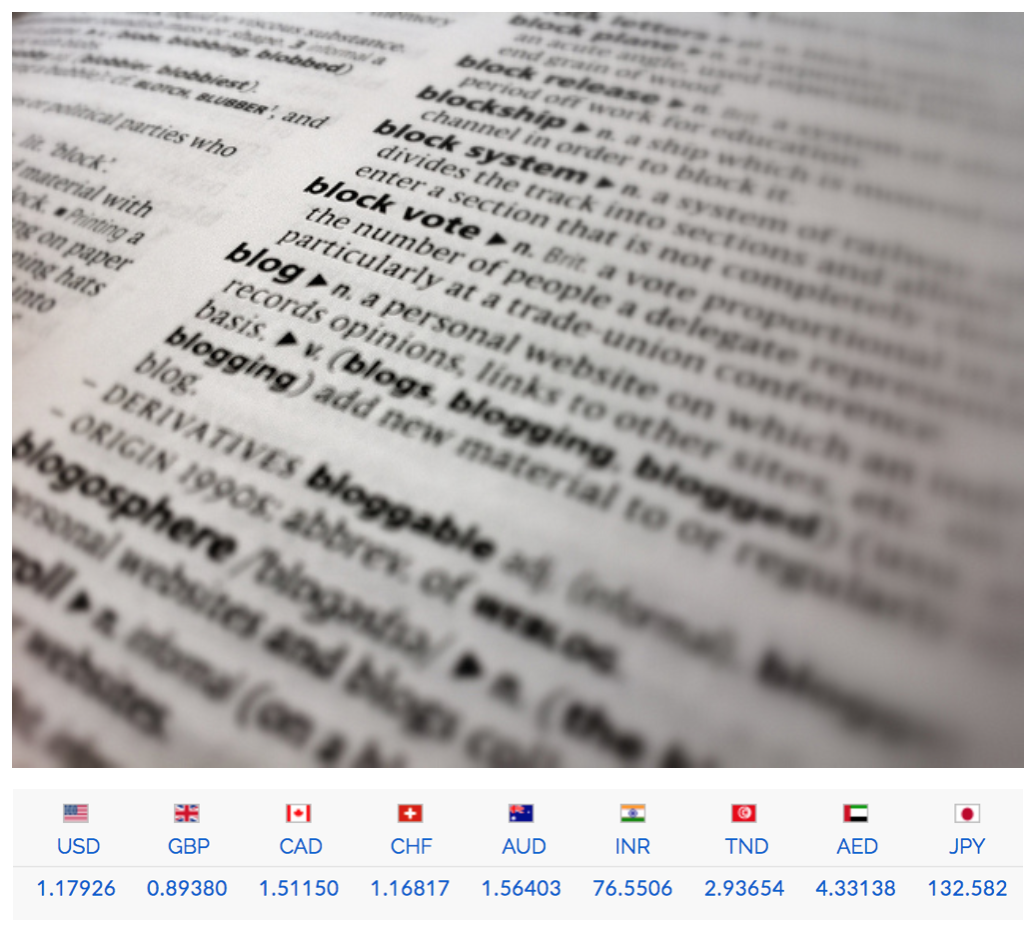

Of course, there exist several real examples of such abstract dictionaries in real-life objects. For instance, in Fig. 31, we show a collection of definitions and a currency exchange table. Both of them are concrete objects that are built starting from the abstract notion of a dictionary.

Fig. 31 Two examples of a dictionary in natural objects are a collection of definitions (top) and a conversion table from 1 euro to the amount in the other nine currencies (bottom). Top picture by Doug Belshaw, source: Flickr. Bottom screenshot from XE.#

as part of the material of the course.# 1my_first_dict = dict() # this creates a new dictionary

2

3# these following two lines add two pairs to the dictionary

4my_first_dict["age"] = 34

5my_first_dict["day of birth"] = 15

6# currently my_first_dict contains two elements:

7# dict({ "age": 34, "day of birth": 15 })

8

9# a dictionary can contain even key-value pairs of different types

10my_first_dict["name"] = "Silvio"

11# now my_first_dict contains:

12# dict({"age": 34, "day of birth": 15, "name": "Silvio"})

13

14del my_first_dict["age"] # it removes the pair with key "age"

15# my_first_dict became:

16# dict({"day of birth": 15, "name": "Silvio"})

17

18my_first_dict.get("age") # get the value associated to "age"

19# the returned result will be None in this case

20

21# the following lines create a new dictionary with two pairs

22my_second_dict = dict()

23my_second_dict["month of birth"] = 12

24my_second_dict["day of birth"] = 28

25

26# it adds a new pair to the current dictionary, and rewrite the value

27# associated to the key "day of birth" with the one specified

28my_first_dict.update(my_second_dict)

29# current status of my_first_dict:

30# dict({"day of birth": 28, "name": "Silvio", "month of birth": 12})

31

32# it stores 3 in my_first_dict_len

33my_first_dict_len = len(my_first_dict)

In Python, a new dictionary can be instantiated using the constructor dict(). For instance, my_first_dict = dict() will create an empty dictionary and associate it with the variable my_first_dict.

We can execute several operations on dictionaries, in particular:

we use the operation

<dictionary>[<key>] = <value>for adding a new pair to the dictionary – for instance, my_first_dictionary["age"] = 34and my_first_dictionary["day of birth"] = 15will add the pairs "age": 34and"day of birth": 15to the dictionary – it is worth mentioning that (a) keys must be either strings, numbers, or tuples, and (b) adding a pair with a key that is already included in the dictionary will overwrite the previously-defined pair;we use the operation

del <dictionary>[<key>]for removing the pair identified by the specified key from the dictionary – for instance,del my_first_dictionary["age"]will remove the pair"age": 34, obtaining, thus, a dictionary with just the pair "day of birth": 15;we use the method

<dictionary>.get(<key>)for getting the value associated to the pair having the specified key in the dictionary – for instance, my_first_dictionary.get("day of birth")will return the number 15, while my_first_dictionary.get("name")will return None since no pairs in the dictionary include the specified key;we use the method

<dictionary>.update(<another_dictionary>)for adding all the pairs included in <another_dictionary>to the current dictionary – for instance, if we have the dictionarymy_second_dictionarycontaining the pairs "month of birth": 12and"day of birth": 28, my_first_dictionary.update(my_second_dictionary)will add the pairs"month of birth": 12to the current dictionary, while the pair"day of birth": 15will be rewritten with "day of birth": 28.

In Listing 35, we show some examples of the use of dictionaries in Python. In particular, we introduce the effect of using all the operations mentioned above.

References#

Jorge Luis Borges. La biblioteca de Babel. In El Jardín de senderos que se bifurcan. Editorial Sur, 1941.

David Joyce. Is the Library of Babel infinite? 2016. URL: https://www.quora.com/Is-the-Library-of-Babel-infinite (visited on 2025-10-09).