Recursion#

This chapter introduces one of the main concepts related to Computational Thinking, i.e. the recursion. The historic hero introduced in these notes is Douglas Hofstadter. He is a cognitive scientist. He wrote one of the best-selling educational books on mathematics, logic and self-references entitled Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid.

Note

The slides for this chapter are available within the book content.

Historic hero: Douglas Hofstadter#

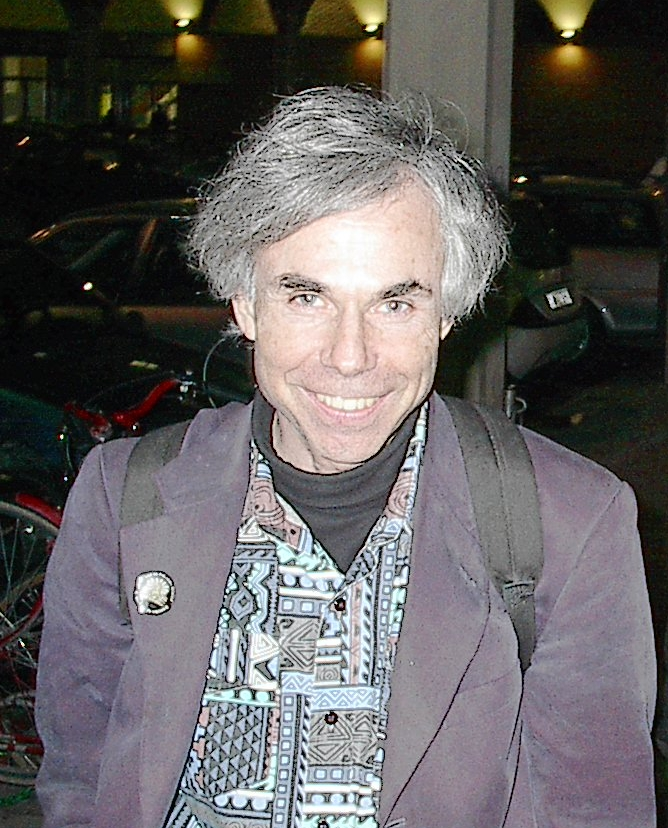

Douglas Richard Hofstadter (see Fig. 32) is a cognitive scientist. His research focuses primarily on the concept of self-reference while being also very active in the fields of consciousness, art, mathematics and physics. He is the author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (a.k.a. GEB), where he investigated in depth the concept of self-reference [Hof79]. In 1980, he received the Pulitzer award for that book in the general nonfiction category.

The book is one of the primary sources of inspiration for choosing to work in the Computer Science field. While Hofstadter is not a computer scientist, one of the central figures of his book is a famous logician, i.e. Kurt Gödel. Gödel provided several contributions also related to the theoretical Computer Science field. In addition, since one of the leading book themes concerns a detailed discussion about the concept of intelligence, the final part of the book discusses the Artificial Intelligence field.

Fig. 32 Douglas Hofstadter in 2002. Picture by Maurizio Codogno, source: Wikimedia Commons.#

Self-reference#

The structure of GEB is an alternation of fictional dialogues and several puzzles. The dialogues are functional to the various topics introduced in the book chapters. The puzzles enable the author to explain the critical behaviour of formal mathematics using easy-listening examples. One of the dialogues is of great interest for this chapter, i.e. the Little Harmonic Labyrinth. In this dialogue, the two main characters, i.e. Achilles and the Tortoise, live a series of adventures in various worlds, starting from the inconsistent composite world described in the Convex and Concave lithograph by Maurits Cornelis Escher. In particular, by using two specific drinks, i.e. the pushing-potion and the popping-tonic, one can enter into a world depicted in an oil painting or any other printed picture and exit from that world, respectively.

One can use these pushing and popping operations within any world. Once entered into the world described in the Convex and Concave lithograph, one can drink another pushing-potion to get into another world depicted by another painting. In this case, though, one needs to drink the popping-tonic twice to come back to the real world. One can start to be lost by doing these pushing and popping operations several times: one could be not entirely sure if the world from which she thinks the journey started is actually the real world since she could have come from another world (and just forgotten about it), and so on. Several stories in the past addressed this specific theme of a journey in a stack of worlds, e.g. in Christopher Nolan’s 2010 movie entitled Inception.

During the journey in several worlds, Achilles and the Tortoise narrate (or are part of) a lot of stories. These stories include citations, references, self-citations and self-references that entangle and even change the whole narrative structure of the dialogue several times. One of the situations concerns Achilles’ use of a magic lamp that allows one to evoke a genie. After rubbing it, a genie appears, and Achilles asks him, as the first wish, the possibility of having one hundred wishes instead of the usual three. The genie answers that he cannot grant any meta-wish (i.e. a wish about a wish). However, the genie tries to solve that request by evoking a new meta-genie from his meta-lamp. Then, the genie asks if the meta-genie and, consequently, GOD (i.e. an acronym for GOD Over Djinn, where the word Djinn is used to designate all the possible genies and meta-genies that can exist) could enable Achilles to ask for a meta-wish. The meta-genie takes his meta-meta-lamp to evoke the meta-meta-genie to answer the genie’s request. Then the meta-genie asks the meta-meta-genie the very same permission, and so on. Once, in the end, Achilles is granted the consent of asking for a meta-wish, he wishes that his wish would not be allowed.

This story contains several pieces of evidence of very well-known and delicate aspects of mathematics and logic. For instance, the acronym GOD used in the story is a recursive acronym. It means that the definition of the acronym contains the acronym itself, thus creating an infinite sequence of acronym rewriting if one tries to disentangle it. For instance, GOD becomes GOD Over Djinn, that becomes GOD Over Djinn Over Djinn, that becomes GOD Over Djinn Over Djinn Over Djinn, and so on. Also, the wish asked by Achilles contains a strange situation: it concerns the denial of the wish itself. This request creates a paradox through a self-reference, i.e. the situation where something (e.g. a sentence or formula) refers to itself.

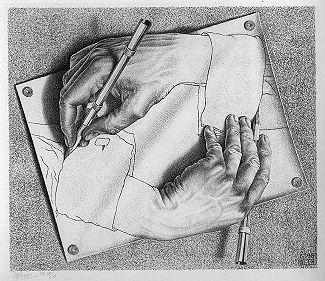

It is worth mentioning that these kinds of self-references may occur in any natural or formal language. For instance, the (meta-)sentence “this sentence is false” exemplifies such a paradoxical situation. Even graphical languages can describe conditions that include self-references. For instance, in the Escher lithograph shown in Fig. 33, two hands are drawing each other. This situation creates a paradox. However, this paradox is just apparent since it exists only in the world depicted by the lithograph. In the real world, there is no paradox since Escher created the lithograph. The take-away message is to beware of self-references. They are powerful tools, but they can also lead to inconsistencies if they are not appropriately tamed.

Fig. 33 Escher’s lithograph entitled Drawing hands. Source: Wikipedia.#

Recursion#

Generally speaking, we have a recursion when something is defined in terms of itself or of its type – i.e. when its definition contains a self-reference. We use recursion effectively in different academic fields, such as cognitive sciences, linguistics, logic, mathematics, physics, and computer science. In this section, we show some well-known adoption of recursion.

In the cognitive science domain, for instance, the study of self-awareness involves recursion by definition. The goal of this cognitive aspect concerns the ability to recognise ourselves as individuals separate from the environment and other individuals. Thus, it is an activity that involves us studying how we appear in the situation we live in. The concept of self-consciousness is closely related to the activity mentioned above. Self-consciousness concerns the recognition of our existence as cognitive agents. These merely philosophical aspects have been explored extensively even in creative works, such as in comics (e.g. Masamune Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell) and movies (e.g. Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner).

The formal grammars introduced in the very first chapter can contain examples of recursive rules as well. Actually, recursive rules are quite typical in the intended formal grammar of programming languages. For instance, consider that we need to specify the formal grammar for handling all the boolean operations and, or and not, as introduced in the second chapter. A reasonable formal grammar is in Listing 36.

1) <boolean_exp> ::= "(" "not" <boolean_exp> ")"

2) <boolean_exp> ::= "(" <boolean_exp> "or" <boolean_exp> ")"

3) <boolean_exp> ::= "(" <boolean_exp> "and" <boolean_exp> ")"

4) <boolean_exp> ::= "True"

5) <boolean_exp> ::= "False"

The non-terminal symbol <boolean_exp> is used in the left-side and right-side of three rules, recursively, for defining all the possible combinations of the boolean operation that can lead to a boolean expression. Thus, by using the grammar above, it is possible, for instance, to create complex boolean expressions like (((True and (not False)) or False) and True). They are actually obtained by using the rules specified in Listing 37.

<boolean_exp>

--3--> (<boolean_exp> and <boolean_exp>)

--4--> (<boolean_exp> and True)

--2--> ((<boolean_exp> or <boolean_exp>) and True)

--5--> ((<boolean_exp> or False) and True)

--3--> (((<boolean_exp> and <boolean_exp>) or False) and True)

--4--> (((True and <boolean_exp>) or False) and True)

--1--> (((True and (not <boolean_exp>)) or False) and True)

--5--> (((True and (not False)) or False) and True)

Even Noam Chomsky argued that recursion is a specific ability and essential property of human language. For instance, each sentence can be a composition of a subject, a verb, and another sentence as objective part, as shown by the formal grammar in Listing 38.

1) <sentence> ::= <subj> <verb> <sentence>

2) <sentence> ::= <subj> <verb> "books"

3) <subj> ::= "Alice"

4) <subj> ::= "Bob"

5) <subj> ::= "Christine"

6) <verb> ::= "thinks"

7) <verb> ::= "said"

8) <verb> ::= "read"

According to the aforementioned rules, and in particular the first one that allows us to build a sequence of linked sentences, it would be possible to write a composite sentence like “Alice thinks that Bob said that Christine read books“. This is possible by applying the aforementioned rules in Listing 39.

<sentence>

--1--> <subj> <verb> <sentence>

--3--> Alice <verb> <sentence>

--6--> Alice thinks <sentence>

--1--> Alice thinks <subj> <verb> <sentence>

--4--> Alice thinks Bob <verb> <sentence>

--7--> Alice thinks Bob said <sentence>

--2--> Alice thinks Bob said <subj> <verb> books

--5--> Alice thinks Bob said Christine <verb> books

--8--> Alice thinks Bob said Christine read books

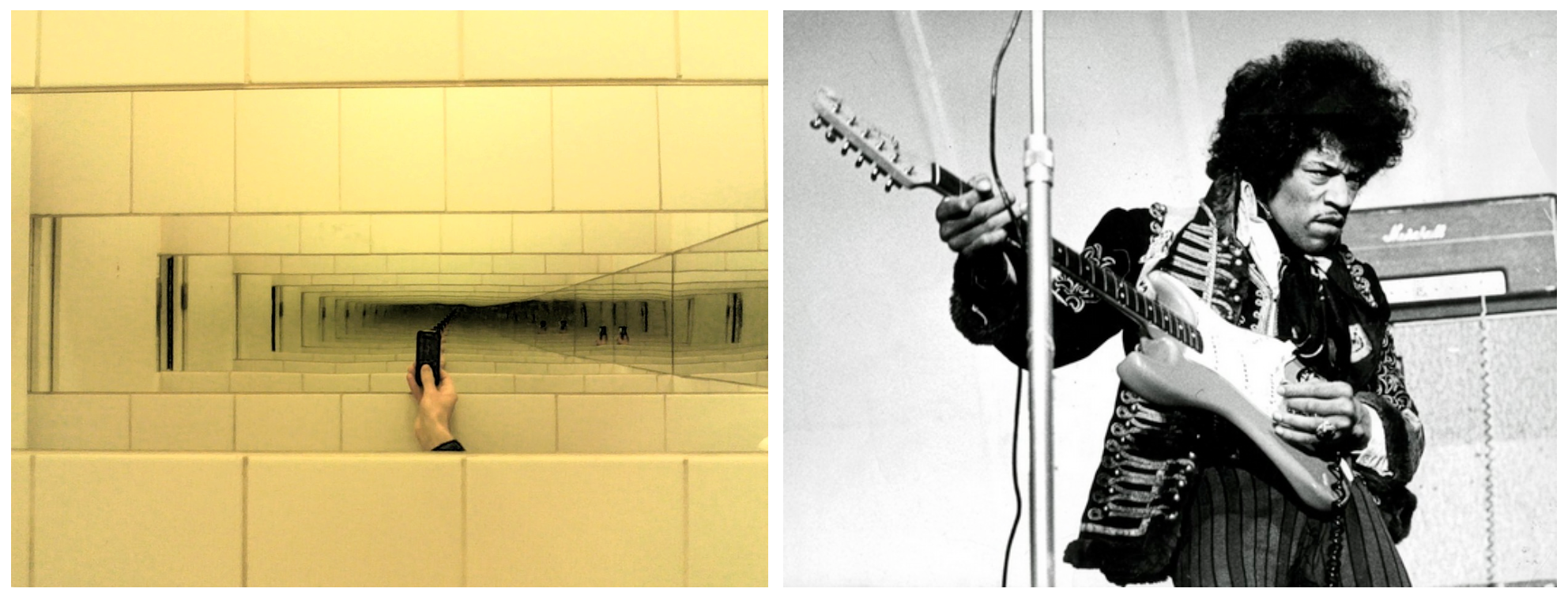

We can find similar recursive situations in physics. Such cases concern well-known scenarios that can happen in our daily life, such as those introduced in Fig. 34. In particular, the left picture shows a situation known as the infinity mirror, created by positioning two mirrors in front of the other to reflect an image indefinitely. On the other hand, the right picture portrays Jimi Hendrix, who mastered the use of the Larsen effect. A Larsen effect happens when an audio output device (e.g. e speaker) amplifies an audio signal received by an audio input device (e.g. the guitar pickup). That amplified signal is then received again by the input device, and so forth, to create an audio loop.

Fig. 34 Two examples of recursion in real-life situations: the infinite mirror (left) and the Larsen effect (right). Left picture by Elsemuko, source: Wikipedia. Right picture source: Wikipedia.#

Recursive functions#

As anticipated in the previous section, the recursion is used (quite extensively) also in Computer Science, and it represents, technically speaking, an alternative to the iteration. In practice, recursion is proper when a solution to a particular computational problem depends on the partial solutions of smaller instances of the same problem. Computer scientists have developed some approaches to tame[1] recursion to avoid infinite loops and thus to use it within algorithms.

In practice, an algorithm has a recursive behaviour when it has one or more basic cases and at least one recursive step. Each basic case describes a terminating scenario and does not use any recursion to produce the answer to a specific (sub-)problem. Instead, the recursive step is where the same algorithm is executed again with a different (and, usually, reduced) input. Listing 40 shows the generic skeleton of a recursive algorithm with one basic condition and one recursive step.

1def <function>(<param_1>, <param_2>, ...):

2 if <base_case_condition>: # BASIC CASE

3 # do something and then…

4

5 # return the basic value

6 return <value>

7 else: # RECURSIVE STEP

8 # do something and then…

9

10

11 # execute the recursive call using different input

12 result = <function>(<param_a>, <param_b>, ...)

13

14

15 # the result of the recursive call is combined

16 # somehow with other information, and then…

17

18 # return the result of the execution of the recursive step

19 return <value>

as part of the material of the course.#1def run_forever_recursive():

2 run_forever_recursive()

It is worth mentioning that the basic case is crucial for allowing the algorithm to stop a certain point. Usually, avoiding the basic case means creating an algorithm that runs forever. For instance, in Listing 41, there is a recursive implementation of the run_forever function we have shown in one previous chapter. The only thing that such a recursive algorithm does is to call itself again, thus creating a loop of calls that never ends.

An example of a simple and complete (basic case + recursive step) recursive algorithm that solves a particular computational problem is that of the multiplication operation. In particular, the multiplication of two integers can be defined as the sum of the first number with itself as many times as indicated by the other number, e.g.: 3 ⋅ 4 = 3 + 3 + 3 + 3. However, looking carefully at the behaviour of this operation, one can also decouple it in terms of a sequence of multiplications summed with each other. In fact n1 ⋅ n2 = n1 + (n1 ⋅ (n2 - 1)) and, by applying the same rule, we can then say that n1 + (n1 ⋅ (n2 - 1)) = n1 + (n1 + (n1 ⋅ ((n2 - 1) - 1))), and so forth until we do not multiply the first number by 0, which is the basic case. For instance, 3 ⋅ 4 can be rewritten as follows by means of the aforementioned rule: 3 ⋅ 4 = 3 + (3 ⋅ 3) = 3 + (3 + (3 ⋅ 2)) = 3 + (3 + (3 + (3 ⋅ 1))) = 3 + (3 + (3 + (3 + (3 ⋅ 0)))) = 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 0 = 12. This mechanism for defining the multiplication is entirely based on a recursive approach, which is illustrated in Listing 42.

as part of the material of the course.# 1# Test case for the algorithm

2def test_multiplication(int_1, int_2, expected):

3 result = multiplication(int_1, int_2)

4 if expected == result:

5 return True

6 else:

7 return False

8

9# Code of the algorithm

10def multiplication(int_1, int_2):

11 if int_2 == 0:

12 return 0

13 else:

14 return int_1 + multiplication(int_1, int_2 - 1)

15

16print(test_multiplication(0, 0, 0))

17print(test_multiplication(1, 0, 0))

18print(test_multiplication(5, 7, 35))

References#

Douglas R. Hofstadter. Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid. Basic Books, New York, NY, USA, 1979. ISBN 0-465-02656-7. URL: https://www.physixfan.com/wp-content/files/GEBen.pdf.

Josh Tyler. The magic of coding: Why programmers are the modern-day wizards. July 2013. URL: https://medium.com/@joshuatyler/the-magic-of-coding-30e58ce31032 (visited on 2025-10-11).